- Home

- Alexandra Bracken

In Time Page 4

In Time Read online

Page 4

“Sure,” I say, worrying that he’s waiting to get an eyeful of my “guest,” waiting to follow her out to the parking lot. Jesus. “That it? Okay, great.”

I slam the door in his face before he can get another word out, and flip the dead bolt over. I watch the guy stand out there for a few more minutes, and don’t turn away until he finally sucks it up and leaves.

Leaning back against the door, I survey what’s left of the groceries I bought two weeks ago. I have a bag of chips, a cup of ramen, a loaf of bread and peanut butter. I don’t realize how hungry I am until I see how little I have to eat. I could try to order something in, but that’s the kind of luxury I know would draw unwanted attention from the other residents of Phyllis’s motel. I can’t go pick something up without leaving the girl alone to potentially escape. She can live with a sandwich. All kids like peanut butter sandwiches.

Unless they’re allergic to peanut butter.

Okay. She gets the ramen. I just have to remember to sit far away while she eats it so she can’t throw the hot broth in my face.

I bend down, pouring the last of the water from the gallon jug into a chipped mug to zap in the microwave. I pour the hot water straight into the Styrofoam container, my stomach gargling at the first whiff of the roast chicken flavoring.

What if she’s a vegetarian?

Shit—no, stop it. She doesn’t get to be a vegetarian.

It is a living thing with needs, but it is not human.

It is a living thing with needs, but it is not human.

It is a living thing with needs, but it is a freak.

It has also been in the bathroom with the water running for the past fifteen minutes. I let my brain get as far as wondering if it’s possible to drown yourself in a sink full of water before I cross the room in two long strides. The door’s lock has been broken since I got here and she has nothing to block the door with.

The first thing I see is the trail of bloodied puffs of toilet paper on the counter. She’s left the water running at full blast, and the drain, which functions at half capacity on a good day, can’t handle this load. The water has breached the shallow basin and is spilling out onto my feet. The vanity lights cast everything in a sour glow.

The kid is sitting on the ground in that little bit of space between the toilet and the shower, her face stubbornly turned away from the door. Her shoulders are still shaking, but the only noise that escapes her is pathetic sniffling. As she scrubs at her face, I realize I never cut the zip tie around her wrists, and I start to get a fluttering panic low in my stomach.

When she does turn to face me, the only trace she was ever crying is in her eyes, which are still a raw pink. The cut across her forehead is finally scabbing over, but she’s managed to reopen the one on her chin.

“Stay here,” I say. “Right there.” I have a tiny first aid kit I bought off the old high school nurse. I don’t know that she was really supposed to be selling her supplies, but we were the last class to graduate before they shut the schools down, so I guess there was no point in pretending she’d need it one day.

The only bandages I have seem absurdly large, but they’ll do as good of a job as any. I tell myself it’s worth it to use them because otherwise the PSFs could dock some of my reward money for “medical costs,” but really, it’s just hard to look at her face like that.

I peel the first one out of the package as the vanity lights begin to buzz and flicker. I glance up at her under my dark bangs. “Don’t zap me. I’ll kick your ass.”

She finally loses that terrible forced blank look and snorts, rolling her eyes.

It’s a quick job that’s not especially gentle, but she sits there and takes it. She doesn’t say a thing. I have to swallow the irritation that comes with it; if the freak would just act out, try something, it would make this whole process that much easier on me. I feel like she’s waiting for me to screw up and make a break for it, or she’s just laughing at how terrible I am at this gig. Laughing like I’m sure the rest of them are back home.

“I made dinner,” I say, mostly to fill the silence. The freak just watches me, her mouth twitching like she might smile, and I know I’m right. She thinks I’m a joke.

Maybe I’m doing this all wrong—I shouldn’t just give her the food. Maybe she should have to earn it through good behavior? I don’t think she’s scared of me. But she should be—she needs to be. She has to know what’s coming.

While she sits and carefully eats the ramen I left for her on the cleared desk to avoid spilling, I take out the knife I swiped from the dead kid and kind of…make a show of twirling it around. But eating with her hands tied like that takes up so much of her concentration, I’m ignored.

By the time she finishes, I can feel the frustration and embarrassment burning just under my skin. I grab her arm and pull her off the chair, working a plan out as I lead her to the bed. I force her down onto the floor, trying not to echo her wince as she sits.

“Don’t move,” I bark, leaving her only long enough to get one pair of handcuffs out of my duffel. The bones of her ankle are tiny enough that I can tighten one end around it and latch the other over the metal bedpost hiding beneath the bed’s ruffled skirt.

And again, she just stares at me the entire time, and I feel my face flush with heat, the way it always used to when I was flustered and on the verge of crying as a dumb kid. The bandage covering her chin exaggerates its point as she tilts her head up.

“Stop it,” I warn her, feeling anger rise like a swarm of hornets in my skull. “Same thing that happened to your friends is gonna happen to you, so you can wipe that stupid look off your face—stop it!”

Jesus, I can’t stand criers. I turn my back as her face crumples, just for a second. And I wonder, in a way that pisses me off all over again, if she was crying in the bathroom because of what I was going to do or what happened to her friends. Not knowing for sure what happened to them, really.

Why were they all traveling together like that, anyway? I swipe the handbook off the nightstand and bend the soft cover between my hands. That other Asian girl—was that her sister? Did her sister really just leave her there to save her own ass? Cold, man. Is that what these abilities do to them? Turn them into animals that know it’s all about survival of the fittest—

STOP. IT.

Because the situation already isn’t uncomfortable enough, 2A, the neighbor to my right, apparently has a guest of his own for the evening. I can feel the bedpost knocking against mine through the wall and scramble to grab the TV remote before the moaning starts. Static, static, static, news, game show rerun…I settle on The Price Is Right and turn the volume way up. This damn freak—I should have just left her, hoped to find one closer to Phoenix. She’s pricked every last one of my nerves with this act of hers, trying to pretend she’s all innocent and sweet to work me over, to put me in this exact place where I feel like I have to make sure she doesn’t have to deal with an ugly thing like that.

There has to be something in the handbook about PSFs being willing to pick up a kid instead of me having to drive to Prescott to drop her off. I don’t like the way my brain keeps circling back to wondering if I should give her one of the pillows or a blanket or if she can send an electric charge through the bed frame and kill me while I’m sleeping.

There’s a brief description in the book about what each color represents, but nothing about the theories of what caused the “mutation,” as they so eloquently put it. Abilities fluctuate in strength and precision depending on the individual Psi. Great. Of course life hands me the one that’s strong and precise enough to KO a car.

It’s sort of amazing to think that for as long as this has been going on, they’re still not any closer to figuring out what caused it or how to fix it. The rest of us would love if Gray would remember he’s supposed to be fixing the economy, too, not just pouring money into research for this supposed virus. What does it matter if we save the “next generation of Americans” when we can barely keep the cu

rrent one going on what little we have? Nobody wants to have kids these days, not when it means potentially losing them a few years later. Birth rates are way down; there’s no immigration into or emigration out of the country because they’re terrified of the virus’s spreading. The future is all they want to talk about these days, not the present. Not how we fix things now. How will America move forward after losing an entire generation? the radio broadcasters want to know. If the Psi can be rehabilitated, how will they handle being reintroduced to society? asks the New York Times. Is this the end of days? cries the televangelist.

Maybe we all die out and the freaks inherit the world. No one seems to want to suggest that possibility, though.

There’s nothing about a PSF pickup in the handbook, of course, though there’s this: If you feel like you are in imminent danger and the Psi you are pursuing is classified as Red, Orange, or Yellow you can request backup from nearby skip tracers through the network. The Psi Special Forces unit and the United States government are not responsible for any reward disputes that may follow.

So…that’s ruled out, seeing as I still have zero access to the skip tracer network.

I roll off the bed, walking the long way around the freak to get to my food hoard and mini-fridge. As I slather peanut butter on the stale bread, I tell myself, Tomorrow you’ll be eating steak. Pizza. Whatever you want. Right now, though, I just feel exhausted at the thought of having to deal with all this again tomorrow. I can’t even psych myself up with the mental image of throwing the bills in the air as I jump on Phyllis’s crappy-ass bed, letting them shower down around me.

The beer might as well have been NyQuil. Gone are the glory days of high school, when I could down bottle after bottle after the Friday-night football games and then stay up late enough to watch the sun rise from the roof of my buddy Ryan’s house. One and done.

I don’t want to think about Ryan, though, or any of them. They left me behind, vanished into a world of black uniforms and secrets. It’s fine. I swear it is. Sometimes, though, I just wish one of them had fought to take me with them. It’s hard to be the person who gets left behind, and never the person who gets to do the leaving.

I’m just starting to drift off to sleep, the handbook open across my chest, when the game show ends. At some point, I must have dozed off, because the next things I’m aware of are Judy Garland’s unmistakable crooning and her big brown eyes meeting mine as I squint at the screen. It’s that famous song about the rainbow—lemon drops, birds, all those nice things. She’s flanked by her little dog and a sepia-toned Midwest sky. The next time my eyelids flutter open, the house is in the tornado, crashing down.

I pat around the bed, searching for the remote just as Dorothy opens the door of her house to the Technicolor world of Oz.

It’s…somehow nicer than I remembered. My dad forced me to watch it with him when I was a little kid, maybe seven or eight, and all I remember thinking was how stupid the special effects were compared to those in the action movie I’d just seen in the theater the night before. I hated everything, even the way Dorothy’s voice seemed to wobble when she talked.

And I swear, the minute that big pink bubble appears and the good witch, whatever her name is, appears in that froufrou dress, I feel the bed jerk as the freak handcuffed to it twists to get closer to the screen.

I prop myself up on my elbows, peering down at her in the dark. She’s rearranged herself so she’s sitting awkwardly on her knees. I know the handcuff must be digging into her skin, but she doesn’t seem bothered by it. Her face is reflected in the TV’s glass face, and even before the Munchkins start singing and parading around, I see her eyes go wide and her lips part in a silent gasp. She’s riveted, like she’s never seen anything like it before. That seems impossible. Who hasn’t watched The Wizard of Oz?

It keeps her quiet and occupied—and to be honest, I’m too lazy to get the remote from where it’s fallen on the floor. So I leave it on and switch off the light on the nightstand. I try to sleep, but I can’t. And it’s not that the TV is on too loud, or that it’s too bright—I actually want to watch this. My brain wants to puzzle out why my dad was so hell-bent on getting me to sit through the whole thing. Like with everything he else loved, I’m searching for him in it. A line he borrowed, some kind of philosophy he gleaned from it…and really, all I can see is how this candy-colored world must have made him happy on the days he could barely bring himself to get out of bed.

I don’t want to think about this—to bring Dad into it now, when I’m already feeling this low. The virus-disease-whatever hit these kids at a young age, but my dad carried his sickness with him his whole sixty years of life, through the good years and the bad ones, and the terrible ones after he lost his restaurant. Until the weight of it finally sank him.

I want to laugh when all the characters start delivering the moral of the story, that all these things they’re looking for have been inside them all along—that that’s where goodness and strength live. They want you to think that darkness or evil is only something that gets inflicted on you by the outside world, but I know better, and I think the freak does, too. Sometimes the darkness lives inside you, and sometimes it wins.

“Now I know I’ve got a heart,” the Tin Man says as I shut my eyes and roll away from the screen, “because it’s breaking.”

The girl has nightmares. It’s the only time I hear her talking, and it scares the shit out of me. I sit straight up in bed, fumbling in the dark for the knife I left on the nightstand. I think a wild dog’s broken in, or one of those feral cats I always see lurking around the motel’s Dumpsters. My brain is still half asleep—well, three-quarters asleep. I don’t remember about the kid sleeping on the floor until I’m basically stepping on her. I don’t even assume the noise is human, because it can’t be. No way. The words that come crawling out of her mouth aren’t words at all, but these gut-wrenching, god-awful moans.

“Nooooo, pleassssssse…nooooooo…”

I stand over her, and stand there and stand there and stand there, and I think, Wake her up, Gabe, just do it, but that feels like a line that shouldn’t be crossed. That means I care.

I don’t. No matter what she does or doesn’t do, no matter how hard she makes this for me, I won’t ever care.

The bed creaks as my weight sinks back down into it. I half hope the noise will wake her and get me out of having to make the decision. One hour drives into the next, and I lie there, as still as I can force myself to be. I listen to her cry all night, and it feels like a punishment I deserve.

FOUR

MORNING comes in a blinding burst of white light as the thick motel curtains are thrown aside, their metal rings screeching in protest. The flood of sun into the dark, musty room is so sudden that my body reacts before my brain does. I drop off the side of the bed and stagger onto my feet, throwing up a hand to shield my eyes.

Shit—shit! I slept too long, what time is it, where’s the—

A few things come into focus quickly. First the pile of clean laundry sitting on top of my duffel bag, just to the left of the door. I can smell the fresh scent from here and take a step toward it, confused. Out of the corner of my eye, I see a small form at the desk, sitting in front of two plates of food—powdered doughnuts, some fruit snacks, and pretzels—with my jar of peanut butter open between them. Clear plastic wrappers are dangling over the edge of the room’s small trash can, caught on the lip. I know exactly where they came from: the vending machines in the laundry room.

Carefully coating each pretzel on her plate with a delicate dab of peanut butter, she keeps her back to me as I walk to the table. The zip tie is gone, and so are the handcuffs. She’s changed, too, out of her dirty, bloodied clothes into a baggy pink Route 66 T-shirt and jeans she’s had to roll up a few times at the ankles. I stare at them until I remember there’s a donation box in the laundry room that no one’s ever done anything with, filled mostly with kid stuff.

With the exception of the bed I just fell out of, th

e room is impeccably tidy. The trash is gone, and she’s even cracked the window open slightly to get fresh, cool air flowing in. I storm to the window and throw the curtains shut. The room is pitched into darkness, but I don’t care. It makes it easier somehow.

“Are you stupid?” I yell. “You think this is going to work on me? That if you play nice with me, I’ll be nice right back? Are you really that big of an idiot that you think I want to help you?”

She shrinks a tiny bit in her chair, but she doesn’t look away. She doesn’t even blink, and I can’t help it—I know she’s a freak, I know that I shouldn’t be talking to her at all, or acknowledging this, or letting her get me this worked up, but it all explodes inside me until I feel anger making a mess of every other thought in my head.

Even if she wasn’t trying to play that game, she obviously thought I couldn’t take care of myself, let alone her. And this was her way of throwing it back in my face, wasn’t it? Mocking me. Why else wouldn’t she have run when she had the chance? Clearly I don’t know how to latch the handcuffs, I don’t know how to restrain her, and I can’t even keep myself alert enough to know when she’s left the goddamn room.

Why did I think I could do this? The freak won’t say a word, but I just look at her and I know the dialogue running through her head. He sucks, he’s dumb as roadkill, he’s better off scrubbing trailers. Same script as everybody else.

But I’m not. I’m not. I swear I’m not.

I can be better than this. I know I can be. These freaks, they all know the right way to mess with your thoughts, make you doubt yourself, but I won’t let her. Not anymore. The clock says that it’s only eight in the morning. They’ll be open. I can get rid of her now and be done with this. Get the ten-ton weight off where it’s caving my chest in.

“This isn’t Kansas, Dorothy,” I snap at her. “People here aren’t nice. They aren’t your friends. I’m not your friend.”

The Darkest Legacy

The Darkest Legacy Sparks Rise

Sparks Rise The Darkest Minds

The Darkest Minds In Time

In Time Star Wars: New Hope: The Princess, the Scoundrel, and the Farm Boy: Being the Story of Luke Skywalker, Darth Vader, and the Rise of the Rebellion (Novel)

Star Wars: New Hope: The Princess, the Scoundrel, and the Farm Boy: Being the Story of Luke Skywalker, Darth Vader, and the Rise of the Rebellion (Novel) Brightly Woven

Brightly Woven Wayfarer

Wayfarer In the Afterlight

In the Afterlight Passenger

Passenger Prosper Redding: The Last Life of Prince Alastor

Prosper Redding: The Last Life of Prince Alastor Never Fade

Never Fade Lore

Lore The Dreadful Tale of Prosper Redding

The Dreadful Tale of Prosper Redding The Darkest Minds: In Time

The Darkest Minds: In Time The Last Life of Prince Alastor

The Last Life of Prince Alastor In the Afterlight (The Darkest Minds series)

In the Afterlight (The Darkest Minds series) In the Afterlight (Bonus Content)

In the Afterlight (Bonus Content) The Darkest Legacy (Darkest Minds Novel, A)

The Darkest Legacy (Darkest Minds Novel, A) Darkest Minds (1) The Darkest Minds

Darkest Minds (1) The Darkest Minds The Princess, the Scoundrel, and the Farm Boy

The Princess, the Scoundrel, and the Farm Boy Never Fade tdm-2

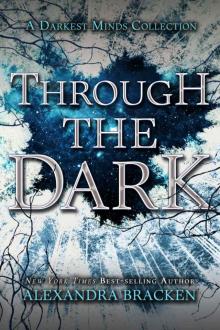

Never Fade tdm-2 Through the Dark (A Darkest Minds Collection) (A Darkest Minds Novel)

Through the Dark (A Darkest Minds Collection) (A Darkest Minds Novel)